Error handling in software engineering is a bit like paying taxes — it’s something that we all have to do and something that nobody enjoys doing…

If you are anything like me, then you are most likely familiar with how tedious and awkward error handling with try / catch statements can feel especially in languages like Javascript & Typescript. Often times I find myself having to write unwieldy code like the following:

function getUrlFromString(urlString: string): URL | undefined {

let url: URL | undefined

try {

url = new URL(urlString)

} catch (error) {

console.warn(`invalid url: ${(error as Error)?.message}`)

try {

url = new URL(`https://${urlString}`)

} catch (error2) {

return undefined

}

}

return url

} And while this might seem like a contrived example or something that could easily be abstracted into smaller utility functions, it might surprise you how many times I’ve see code just like this in production software.

What I do like about the code snippet above is that it demonstrates several key issues with the try / catch pattern, especially relating to Typescript:

- values are scoped to their respective blocks

- errors are not guaranteed to be an

Errorinstance - retry logic can become extremely verbose

- it isn’t clear when something can throw

Since any function can throw from somewhere deep in the call stack, the control flow of the program can become unpredictable and hard to reason about. In fact, let’s take a look at one more example. What do you think this function will return?

function generateOddNumbers(count: number) {

let oddNumbers: number[] = new Array(count).fill(0)

try {

// generate an array of random numbers

oddNumbers = oddNumbers.map((_, i) => Math.floor(Math.random() * i))

// check if they are all odd and return or throw

if (oddNumbers.every((num) => num % 2 === 1)) {

return oddNumbers

} else {

throw 'Invalid sequence'

}

} catch (e) {

// handle errors

console.warn(`Error generating numbers: ${e}`)

return false

} finally {

// cleanup resource

console.log('cleaning up resources...')

oddNumbers = []

return

}

} Perhaps you might have guessed that when the argument count is small enough it might return an array of only odd numbers once in a while. That would make send right?

Well if you guessed undefined for any number, you would be correct. This is because the finally block will always execute after the try and catch blocks, no matter what.

The try…catch statement is comprised of a try block and either a catch block, a finally block, or both. The code in the try block is executed first, and if it throws an exception, the code in the catch block will be executed. The code in the finally block will always be executed before control flow exits the entire construct. [source]

If this seems confusing to you, don’t worry you are not alone.

A better way?

If you are familiar with other programming languages like Go or Rust, then you probably already know where I am going with this — errors as values.

Instead of throwing errors willy-nilly to whoever will catch them, the idea is to treat errors as first class citizens and handle them as close to the call site as possible. While this article isn’t a deep dive into the errors as values paradigm, a lot of the techniques for code written in this article have been inspired by Rust.

Now let’s start coding a re-usable solution which can help simplify our error handling logic. Since this will be in Typescript let’s begin by describing the shape of our data, which should either be a generic value T or the concrete Error class, but not both.

type ResultOk<T> = [T, undefined]

type ResultError = [undefined, Error]

type Result<T> = ResultOk<T> | ResultError The above types are just tuples which either contain the generic value T or undefined in the first position and Error or undefined in the second position. The last type is a discriminated union of both the ResultOk<T> and ResultError types.

Next we will create a simple utility function which takes a function as an argument, execute that function inside a try/catch expression, and returns the output wrapped in our Result<T> type:

function tryCatch<T>(fn: () => T | never): Result<T> {

try {

const value = fn()

return [value, undefined] as ResultOk<T>

} catch (e) {

const error = e instanceof Error ? e : new Error(String(e))

return [undefined, error] as ResultError

}

} If the function throws then the exception will be caught and converted to an error if needed, otherwise it will return the value. Since each branch returns a type which is narrower than the Result<T> the result tuple is easy to unpack and check for errors.

const [url, error] = tryCatch(() => new URL(maybeUrl))

if (error) return console.warn(error.message)

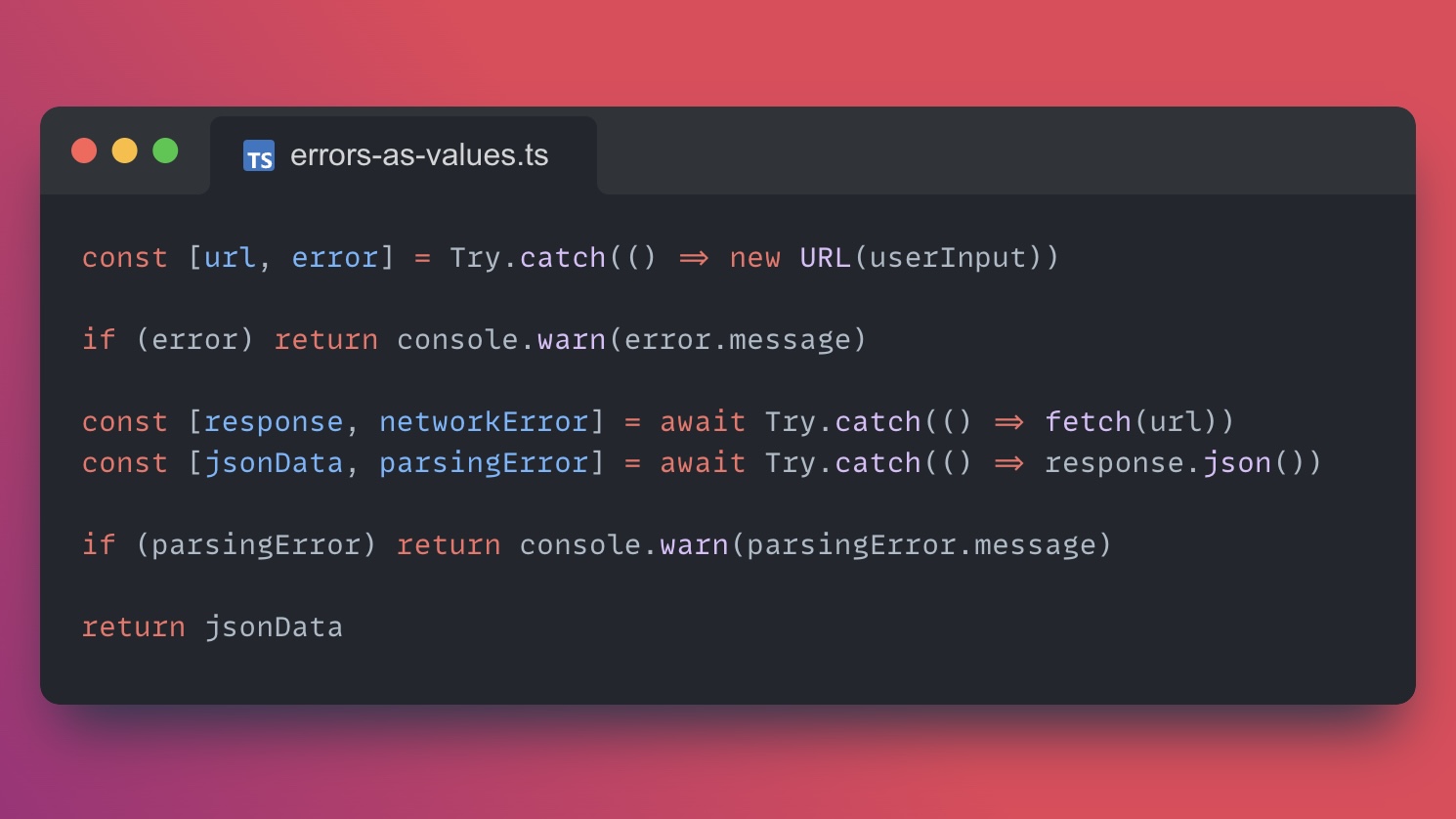

return url.href // type-safe! By checking if the error value is defined and early returning if so, the Typescript type system is able to infer that url must be defined below, because error will only be defined when Result<T> is [undefined, Error] ! Now let’s revisit the same problem I mentioned in the beginning of this article and see how this approach does:

function getUrlFromString(urlString: string): URL | undefined {

let [url1, err1] = tryCatch(() => new URL(urlString))

if (!err1) return url

else console.warn(err1.message)

let [url2, err2] = tryCatch(() => new URL(`https://${urlString}`))

if (!err2) return url2

else console.warn(err2.message)

let [url3, err3] = tryCatch(() => new URL(`https://${urlString}`).trim())

if (!err3) return url3

else console.warn(err3.message)

} Just like that our getUrlFromString(urlString) is far more succinct and easy to follow, so much so that we were able to add another case to make the program even more robust!

The less time we spend fiddling with nested try/catch statements, casting errors and wrangling control flow; the more time we can spend on making programs which crash less!

Synchronous vs. Asynchronous

So far the tryCatch utility works great for synchronous error handling. However, most of the time errors tend to stem from asynchronous operations like fetch() requests and JSON decoding. Here is where we run into a little issue with the type system…

const result = tryCatch(async () => {

return JSON.parse('[1, 2, 3]') as number[]

})

typeof result // Result<Promise<number[]>> The problem is that the promise is now inside our result Result<Promise<number[]>> and thus needs to be unpacked before we can call await. However, this also causes another issue as calling await on the result value can throw! Instead what we would like is for the return type to be Promise<Result<number[]>> so we can do the following:

const [data, error] = await tryCatch(async () => {

return JSON.parse('[1, 2, 3]') as number[]

})

if (!error) {

return data.map((num) => num * 10)

} While we could just create another utility like tryCatchAsync(fn) that fits these constraints, just look at that beautiful example above, that’s what we want — not that “we have error values at home nonsense”.

Advanced Types

Just like before, let’s start by describing what it is we want via types. We know what the async type should be from above example, but how can we translate this to our code? Well the first thing to understand is that async / await is merely just syntactic sugar around promises*.

function example1() {

return new Promise<string>((resolve) => resolve('abc'))

}

async function example2() {

return 'hello'

}

type PromiseType = typeof example1 // () => Promise<string>

type AsyncFnType = typeof example1 // () => Promise<string> This means that theoretically all we need to do is adjust our tryCatch(fn) to distinguish between T and Promise<T> . If we notice that the return type is a Promise , then we can assume the function should be considered async.

function tryCatch<T>(

fn: () => Promise<T> | T | never

): Result<Promise<T>> | Result<T> {

// ...

} Unfortunately, this is where things start getting a bit complicated. If you hover over the result type now you will see the following:

const result = tryCatch(someFunc)

typeof result // ResultError | ResultOk<number[]> | ResultOk<Promise<number[]>> The issue is the type system isn’t able to narrow the type simply by placing an await statement in front of the try/catch. This means functions which should only be synchronous are now appearing as potentially async and vis-versa…

We need to find a way to narrow the type system such that promises are only returned for async functions and not for the synchronous ones, while async functions should only return promises and never synchronous results.

Having tinkered with this problem for longer than I would like to admit and making marginal gains in one area only to regress in others, for a time I thought the technology simply didn’t exist, until one day I stumbled across the following code snippet:

// https://github.com/markedjs/marked

const example1 = marked.render(markdown, { async: false })

const example2 = marked.render(markdown, { async: true })

typeof example1 // string

typeof example2 // Promise<string> A library that was able to return either sync or async values simply by changing the value of an argument! This discovery re-ignited my unyielding thirst for a truly isomorphic try / catch helper and sent me into overdrive. Quickly, I rushed to the Github source code and began trawling through every line until finally I noticed the secret…

Function Overloading

Function overloading in Typescript is most likely one of those things you probably never think about unless you are a library maintainer or deep in the weeds. It allows for defining multiple variants of the same function (or method) with different arguments and return types.

For example imagine we have two similar functions which either add two numbers together or concat two strings. The implementation is nearly identical and it would be nice if we just had two write this logic once. The issue we want to avoid is allowing our new add(a, b) function to add a number to a string or vis-versa.

function addString(x: string, y: string): string {

return x + y

}

function addNumber(x: number, y: number): number {

return x + y

} This is where function overloading comes in handy, we can declare multiple versions of the same function to help the Typescript type system narrow the return type. The caveat is that the actual implementation must contain the most permissive type which can accommodate any of the values also passed to the overloads.

function add(x: number, y: number): number

function add(x: string, y: string): string

function add(x: number | string, y: number | string): number | string {

if (typeof x === 'string' && typeof y === 'string') return x + y

if (typeof x === 'number' && typeof y === 'number') return x + y

throw new Error('Mismatched types!')

}

add(123, 456) // ok!

add('a', 'b') // ok!

add(123, 'b') // type-error

add('a', 456) // type-error As you can see we had to jump through a lot of hoops just to get this simple example working, but it illustrates how function overloading can be used to declare multiple type variants of the same function. The first two function definition are recognized by the type system as overloads, where the last definition handles the actual implementation.

Bringing this back to the tryCatch(fn) helper, let’s see how we can leverage function overloads to help distinguish between the synchronous and asynchronous versions of our function.

function tryCatch<T>(fn: () => Promise<T>): Promise<Result<T>>

function tryCatch<T>(fn: () => T | never): Result<T>

function tryCatch<T>(

fn: () => T | never | Promise<T>

): Result<T> | Promise<Result<T>> {

// ...

} The first function overload handles our async case where the fn argument returns a promise, this version should also return a promise which can then be awaited to obtain our result tuple containing T or Error . The second overload handles our synchronous case where the fn argument either returns T or never (can throw). Finally the last overload combines all three and the actual function implementation.

Ok, this is starting to look fairly promising if I do say so myself… all that is left now is the logic. The tricky part here is figuring out how to perform a runtime check for an async function and then how to apply our error catching logic to and async function in a synchronous context. Luckily, this is actually what promises are in the first place!

try {

const output = fn()

if (output instanceof Promise) {

return output

.then((value) => [value, undefined] as ResultOk<T>)

.catch((error) => [undefined, error] as ResultError)

}

return [output, undefined] as ResultOk<T>

} catch (e) {

const error = e instanceof Error ? e : new Error(String(e))

return [undefined, error] as ResultError

} The first step is execute the fn() argument and check if output is an instance of a promise. We can do this using the instanceof operator and if true we can call the .then() and .catch() methods to extract the value and construct our result tuple! This will then return our desired type Promise<Result<T>> when awaited!

We are almost there now, but as some of you might have already noticed, we haven’t properly coerced the async error value into the Error class. Let’s extract the logic we used below in the original version into a separate helper which can be used by both versions.

const toError = (e: unknown): Error =>

e instanceof Error ? e : new Error(String(e)) It’s not perfect, but it gets the job done for now. Basically, it just checks if the error value is already an instance of the Error class and if so does nothing, otherwise it converts the value to a string which is then used to instantiate a new Error . Tying this altogether we should have something that looks like the following:

// our result types...

type ResultOk<T> = [T, undefined]

type ResultError = [undefined, Error]

type Result<T> = ResultOk<T> | ResultError

// our error handling utility...

const toError = (e: unknown): Error =>

e instanceof Error ? e : new Error(String(e))

// our try/catch overloads and implementation...

function tryCatch<T>(fn: () => Promise<T>): Promise<Result<T>>

function tryCatch<T>(fn: () => T | never): Result<T>

function tryCatch<T>(

fn: () => T | never | Promise<T>

): Result<T> | Promise<Result<T>> {

try {

const output = fn()

if (output instanceof Promise) {

return output

.then((value) => [value, undefined] as ResultOk<T>)

.catch((error) => [undefined, toError(error)] as ResultError)

}

return [output, undefined] as ResultOk<T>

} catch (e) {

return [undefined, toError(e)] as ResultError

}

} Let’s go ahead and test this implementation with a couple different variations to ensure our types are working properly and the code does what is expected for both synchronous and asynchronous operations! Below I’ve added test cases for synchronous, asynchronous and promise based fn arguments. For each different variant I’ve included one that throws and one that returns successfully:

async function main() {

const result0 = tryCatch(() => 123)

const result1 = tryCatch(() => {

if (Math.random() < 1.0) throw new Error('thrown sync')

return 123

})

const result2 = await tryCatch(async () => 'abc')

const result3 = await tryCatch(async () => {

throw new Error('thrown async')

})

const result4 = await tryCatch(() => new Promise<boolean>((res) => res(true)))

const result5 = await tryCatch(

() => new Promise((_, reject) => reject('thrown promise'))

)

// output the all the results once finished...

const outputs = [result0, result1, result2, result3, result4, result5]

outputs.forEach((info, i) => console.log(`Test #${i}: `, info))

} Looking at this code in a code editor shows that each of the results indeed have the desired return type, please note that some additional type casting needs to be done for the promises. Running this code also outputs what we expect as well:

[LOG] Test #0: [123, undefined]

[LOG] Test #1: [undefined, thrown sync]

[LOG] Test #2: ["abc", undefined]

[LOG] Test #3: [undefined, thrown async]

[LOG] Test #4: [true, undefined]

[LOG] Test #5: [undefined, thrown promise] The result types are looking good and the implementation is working as expected! Lastly, let’s try adding some edge-cases to make sure we haven’t missed anything. Let’s test the following:

- What happens if

fn()doesn’t return or throw anything - What happens if

fn()returns anErrorinstead of throwing - What happens if

fn()never returns and only throws

const result6 = tryCatch(() => {})

const result7 = tryCatch(() => new Error('error as value'))

const result8 = tryCatch(() => {

throw new Error('123')

}) The first two edge-cases appear to work as we might expect, the first one returns Result<void> and the second returns Result<Error> , which is reasonable as our function is only concerned with catching errors, but not if the value they return is an error per se. However, for result8 we can see something funky…

// this wasn't from an async function?!

const result8: Promise<Result<unknown>> Oh no, what is happening here? Well since this function never returns a value, the signature for the fn looks like the following fn: () => never , which can’t easily be matched by our current function overloads. No worries, the fix is quite simple and we just need to add the following overload:

// handle edge case where function never returns

function tryCatch<T>(fn: () => never): ResultError Since the function never returns, this means it must throw and thus we can specify the return type to always be the sync ResultError . Thankfully, we only need to add this for sync version as the async version will still always return a promise first.

Finally, after the all the things we’ve tried, we were able to catch a break and create the fabled isomorphic try/catch utility. Well, at least that’s what I call it anyways. Isomorphic in this context meaning:

An isomorphic function, or isomorphism, is a bijection (one-to-one and onto mapping) between two sets or structures that preserves the relevant properties or operations of those structures. In simpler terms, it’s a way of showing that two things are essentially the same, even if they look different, by establishing a perfect match between their elements while maintaining their underlying relationships.

Which I found as a fitting way to describe the relationship between the try/catch utility behaving the same in both synchronous and asynchronous contexts. What’s even more fitting is that usually function overloading is meant for polymorphism…

Anyways, I hope you enjoyed this article and learned something along the way. The next step is expand on the actual result type, with special methods like .unwrap() and or() , but I will save that for the next article.

You can play around with a live example of the code here on the Typescript playground or view the full source code on my Github.

Thanks again for reading and if you have any questions, comments or suggestions feel free to reach out to me on X or Github; happy coding!

UPDATE: This code is now available as a npm package: https://www.npmjs.com/package/@asleepace/try

# install npm package

npm i @asleepace/try