The other day I was browsing LinkedIn and came across the following post

👌 A common coding question in Javascript interviews: Write a function that implements range WITHOUT using loops?

Unable to resist the urge to write some needlessly complex and over-engineered code, I began weighing my options. Initially, my mind went to recursion. Then to recursion, then to recursion…

function range(a: number, b: number): number[] {

return a < b ? [a, ...range(a + 1, b)] : [b]

} Try it on the TypeScript playground!

However, this was widely boring and severely unambitious; No, what I needed was something with a bit more spice…

Generator Experiments

Then it hit me! Let’s use that thing I always want to use, but literally can never find a good enough reason. That’s right, the good ‘ol Generator.

The Generator object is returned by a generator function and it conforms to both the iterable protocol and the iterator protocol. Generator is a subclass of the hidden Iterator class. Source

It had been a while since I last touched these pointy starred wonders, and so I got to experimenting to refresh my memory.

function* range() {

yield 1

yield 2

yield 3

yield 4

yield 5

}

console.log(...range()) // 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 But, then it dawned on me that I normally use a loop inside a generator! The solution would have to bring back our old friend recursion, recursion, recursion!

function* range(a: number, b: number) {

if (a > b) return

yield a

yield* range(a + 1, b)

} Hmmm… the code was working, but TypeScript wasn’t pleased. A few prayers to the TypeGod’s and a couple minutes hours later I had finished at last, and was eagerly awaiting to dunk on the LinkedIn n00bs!

type RangeIterator = Generator<number, void, undefined>

function* range(a: number, b: number): RangeIterator {

if (a > b) return

yield a

yield* range(a + 1, b)

}

console.log(...range(1, 5)) // 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Try it on the TypeScript playground!

How it works?

While the above code may look foreign to the unsuspecting LinkedIn denizen, it actually isn’t all that complicated. The key takeaway here is how we can abuse the spread ... operator to spread them cheeks.

Let’s take a look at the execution flow starting from console.log(...range(1, 5))

range(1, 5) // Step 1: called (move inside context)

if (a > b) return // (1 > 5) is false so we continue

yield a // pause execution, return (1) to the caller, then resume

yield* range(a + 1, b) // pause execution, return iteration from range(2, 5), then resume

range(2, 5) // Step 2: called (move inside context)

if (a > b) return // (2 > 5) is false so we continue

yield a // pause execution, return (2) to the caller, then resume

yield* range(a + 1, b) // pause execution, return iteration from range(3, 5), then resume

range(3, 5) // Step 3: called (move inside context)

if (a > b) return // (3 > 5) is false so we continue

yield a // pause execution, return (3) to the caller, then resume

yield* range(a + 1, b) // pause execution, return iteration from range(4, 5), then resume

range(4, 5) // Step 4: called (move inside context)

if (a > b) return // (4 > 5) is false so we continue

yield a // pause execution, return (4) to the caller, then resume

yield* range(a + 1, b) // pause execution, return iteration from range(5, 5), then resume

range(5, 5) // Step 5: called (move inside context)

if (a > b) return // (5 > 5) is false so we continue

yield a // pause execution, return (5) to the caller, then resume

yield* range(a + 1, b) // pause execution, return iteration from range(6, 5), then resume

range(6, 5) // Step 6: called (move inside context)

if (a > b) return // (6 > 5) is true so we return which ends the iterator

// Moving backwards through the call stack we get

//

// [1, [2, [3, [4, [5]]]]]

// [1, [2, [3, [4, 5]]]]

// [1, [2, [3, 4, 5]]]

// [1, [2, 3, 4, 5]]

// [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

// Which more or less simplifies to the following expression, note the

// star (*) operator is used to spread the values from the iterator,

// just omitting here the the sake of brevity

function* range(1, 5) {

yield (((((yield 1), yield 2), yield 3), yield 4), yield 5)

}

// Then back in Step 1: context

yield* [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

// Which returns 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 to the caller (...)

console.log(...[1, 2, 3, 4, 5])

// 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 - We call

range(1, 5)which creates our iterator - The

...operator does the dirty work of iterating - The iterator will continue until

returnhas been called - The first pass

a = 1andb = 5- Since

a > bisfalsewe continue - Next we

yield awhich is1to the output - Next we

yield*which returns another generator (step #4)

- Since

- The second pass

a = 2andb = 5- Since

a > bisfalsewe continue - Next we

yield awhich is2to the output - Next we

yield*which returns another generator ()

- Since

- This continues until

a > bandreturn - This tells the iterator we are done!

- Leaving us with

1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Or an even more simplified way to think about this

yieldpauses / resumes the iterator and returns a value to the calleryield*delegate to another iterable object, such as a Generator.returntells the iterator we are done

Final thoughts

While this code would most certainly be rejected on any production pull request, it was a fun example of leveraging some seldom used parts TypeScript which are quite cool, and this is just the surface!

The way I like to think about generators is that they are functions with state, which can pause /resume execution and even have values passed back-in from the caller. They are used quite heavily in libraries like react-redux and also have support for async via the AsyncGenerator . You can learn more about them here or feel free to ask me any questions!

- Mozilla Docs: Generator

- Mozilla Docs: AsyncGenerator

- Mozilla Docs: Spread Syntax

- Mozilla Docs: Yield

- Mozilla Docs: Yield*

That’s cool, but can you?

My original post succeeded in stirring up quite the controversy from folks all across the software engineering spectrum, and one comment caught my attention in particular:

Everything uses a loop under the hood, unless it’s using tensors.

— Some AI Engineer

While this is probably unavoidable to some degree, one thing that still bothered me was that the iterator solution was not all that much different from the original recursive solution. What if we change the problem slightly to include the following:

Implement a range WITHOUT using loops or recursion.

Now things are getting interesting! Just to add a little more context, the comment section had already ruled out using the usual higher order functional such as .forEach , .map , .filter , .reduce , etc.

Array.from({ length: finish - start + 1 }, (_, i) => start + i + 1)

// or

[...Array(finish - start + 1)].map((_, i) => start + i)] While these are short and concise solutions, they are still using loops under the hood. So, I decided to take it a step further and see if I could implement a solution without using loops or recursion.

YCombinator + Generators

Some of you may be familiar with the name YCombinator as it is indeed the same as the venture capital firm, but did you know that it also has a deeper meaning?

The YCombinator is a higher-order function which allows you to write recursive functions without using recursion. It is a concept from the field of computer science and is often used in functional programming languages.

Equipped with this we now have everything we need to implement a solution without loops or recursion! Feast your eyes…

type Y = (next: Y) => (x: number, y: number) => Generator

function YCombinator(f: Y) {

return ((g: Y) => g(g))((g: Y) =>

f(() => (x: number, y: number) => g(g)(x, y))

)

}

const range = YCombinator(

(next: Y) =>

function* (x: number, y: number) {

if (x > y) return

yield x

yield* next(next)(x + 1, y)

}

)

console.log(...range(3, 9)) // 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Try it on the TypeScript playground!

If you want to lean more about the YCombinator I recommend checking out the following blog post which does an excellent job of breaking it down and explaining it step by step!

Happily ever after?

As you can imagine I was riding pretty high after writing potentially the most needlessly complex and over-engineered code to dunk on Jr. devs on LinkedIn when the unthinkable happened…

Interesting approach.

Unfortunately, you can easily encounter:

[ERR]: Maximum call stack size exceeded

Be careful with recursion in Javascript.— Principal Software Engineer at Microsoft

And just like that my reality was shattered.

All the new found joy of working through the mind-boggling intricacies of implementing the Y-Combinator for the first time quickly evaporated. Someone had come along a blew the stack off my code by creating a range over 9,000. At this moment I remembered the wise words once told to me long ago

“For thou who hath not been dunked on, let him cast the first lineth of code” ~ Ancient Proverbs

The Correct Way?

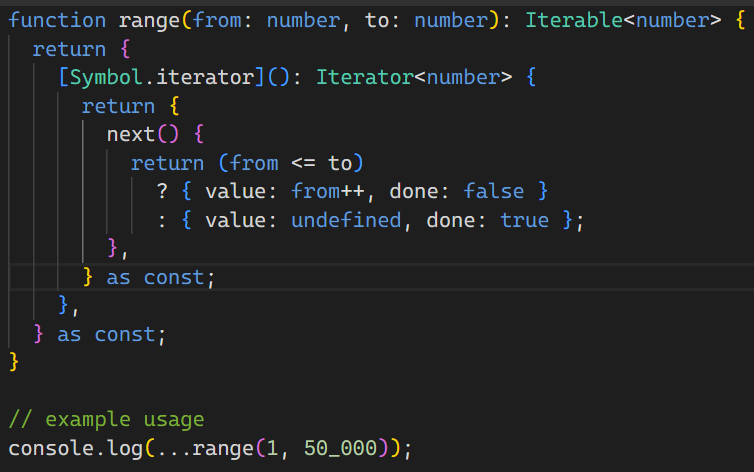

The Microsoft engineer then proceeded to drop this magnificent specimen of code, which could not only easily handle 9,000+ iterations, but relied solely on the built-in mechanics of iterables.

In Javascript, an Iterable can be …spread or used in a for loop. It implements a method named by Symbol.iterator, returning an Iterator. Iterator implements a method next, returning an object containing a value property and a done property, used to control the loop. Jaime Leonardo Pinheiro

It just goes to show there’s always someone out there who knows more than you, and that’s okay! It’s all part of the learning process. I’m grateful for the opportunity to learn from others and to be able to share my own knowledge with the community.

Notable Mentions?

// the changes are slim, but not zero...

const sequence = String(Math.random())

const regex = new RegExp(`^(?=\d{4}$)0?1?2?3?4?5?6?7?8?9?`)

sequence.match()